New Natural Detergent Discovered at UC Davis

The UC Davis College of Agricultural and Environmental Sciences recently published a story about discovery of a new detergent using yeasts from the Phaff Yeast Culture Collection. Some details were edited out in the interest of space. This version of the story contains those missing details – including how an error when ordering lab supplies led to a new discovery.

A new, environmentally friendly detergent will soon reach the market thanks to thousands of yeast samples preserved for many decades at the University of California, sharp-eyed lab researchers, a campus that nurtures interdisciplinary research, a California startup company that recognized the potential of this new product, and … a mistake made when ordering lab supplies in a hurry.

Kyria Boundy-Mills at the University of California Davis has studied microbial oils using yeast strains from the Phaff Yeast Culture Collection since 2011. This collection is the fourth largest public collection of wild yeasts in the world, with over 10,000 strains belonging to 1,500 different yeast species, gathered and preserved throughout decades of yeast ecology research. In 2014, lab manager Irnayuli Sitepu and graduate student Antonio Garay asked Boundy-Mills to order some more flasks so they could grow more yeast cultures as part of their studies of yeasts that make and store oils. Researchers have studied these types of yeasts for many decades, growing cultures in standard Erlenmeyer flasks. Because Boundy-Mills made a mistake in the order, the flasks that arrived were baffled flasks, meaning they had vertical ridges down the sides. These types of flasks are used when microbes need more oxygen to grow well. Sitepu and Garay used the baffled flasks anyway, and noticed something peculiar in one of the liquid yeast cultures: tiny droplets of oil, just visible to the naked eye. And, the droplets of oil did not float, they sank to the bottom of the flask. Oils are supposed to float, so they knew this substance was something unusual.

Tapping the diversity of yeast species in the Phaff collection, when related yeast species were grown in baffled flasks, several other species also secreted these strange oily droplets.

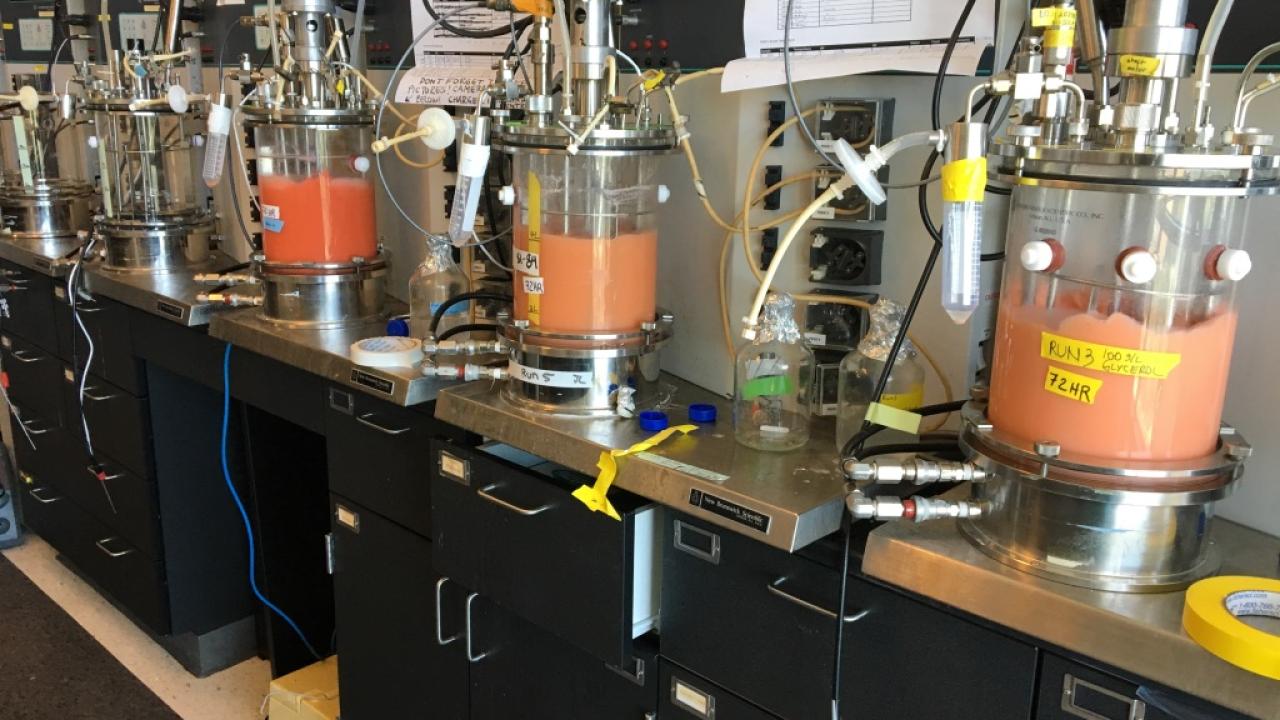

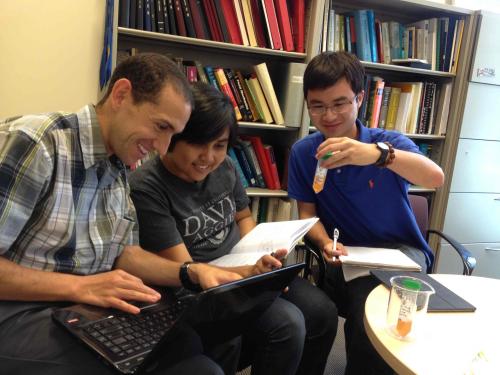

What happened over the next several years illustrates the power of interdisciplinary research, which is nurtured and strongly encouraged here at UC Davis. David Block in the Viticulture and Enology department trained Garay and Sitepu in the use of his lab’s bioreactors, which allowed them to grow larger volumes of yeast cultures and make enough of this new oil for further study.

Tomas Cajka in Oliver Fiehn’s group at the West Coast Metabolomics Center determined that this strange oil was a glycolipid, a molecule that is half fat and half sugar. Molecules with this characteristic of having a water-loving end and a fat-loving end often make good biosurfactants, which are naturally-produced chemicals that have detergent, emulsification, and/or dispersing activity. Garay and Sitepu along with Cajka found that different yeast species made similar, but slightly different, mixtures of these molecules. Master’s student Kevin Xu in Stephanie Dungan’s lab in the Food Science and Technology department determined that these glycolipid biosurfactants strongly reduced water tension at very low concentrations, and could be used as emulsifiers that can form water-in-oil emulsions.

Brewing professor Charlie Bamforth (aka “The Pope of Foam”) found that the glycolipids had antifoam activity near that of commercial antifoam agents. This package of knowledge made the biosurfactant appealing for commercial licensing.

In 2024, this exciting new biosurfactant platform was licensed for commercialization to Ruby Bio, a San Francisco Bay area startup company co-founded by Charlie Silver and Pavan Kambam with deep expertise in biomanufacturing. Ruby Bio has developed applications in home care, personal care, food products, and other end markets. The company has demonstrated that the technology outperforms all other biosurfactants in applications for cleaning and detergency. The performance has even been shown to match that of many conventional surfactants that are routinely used in consumer products, with the further advantage of being more gentle to the skin. Ruby Bio is scaling up production and registering the biosurfactants for commercial use, and the company has begun providing samples to major consumer brands that hope to provide consumers with the most sustainable and non-toxic products available.

Some day soon you may find these biosurfactants in your shampoo, laundry detergent, or dish soap, powered by natural ingredients that are gentle to the environment as well as your skin. It all started thanks to UC Davis’ deep and sustained commitment to scientific research and fruitful collaboration across multiple fields of study. This discovery was possible thanks to campus support of the Phaff collection for many generations.